If you consume news, even casually, you’ll have noticed that many headlines over the last few weeks have been concerned with high temperatures nationwide. “Even places not known for heat, such as Northern California and Alaska, are recording unusually high temperatures this summer,” the New York Times said Thursday, adding that “about 90.5 million people—or 27 percent of the U.S. population—live in areas expected to experience dangerous levels of heat” that day. Phoenix just broke a 49-year-old record, recording 19 consecutive days of temperatures at or above 110 degrees. Even coastal water—a historically reliable source for cooling off—has reached almost 100 degrees in Florida, and in Phoenix, homeless people “have been suffering second-degree burns after they pass out or fall asleep on the hot asphalt and sidewalks,” the Times reports. July was the hottest month on record, globally. So how hot can things get? How much heat can the body endure? Along with the news headlines, scientists have been sounding the alarm about extreme heat. One group of experts say we’re using the wrong metrics to determine how dangerous heat can be.

“Heat waves are becoming supercharged as the climate changes – lasting longer, becoming more frequent and getting just plain hotter,” a group of scientists reported on CBS News. “One question a lot of people are asking is: ‘When will it get too hot for normal daily activity as we know it, even for young, healthy adults?'”

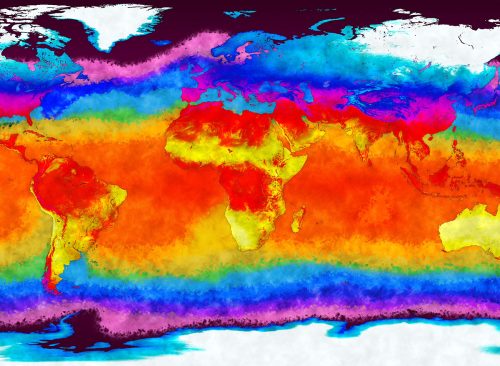

Anyone who’s stepped out into 80-degree temperatures and found it hard to breathe won’t be surprised at part of their conclusions. “The answer goes beyond the temperature you see on the thermometer. It’s also about humidity. Our research is designed to come up with the combination of the two, measured as ‘wet-bulb temperature.’ Together, heat and humidity put people at greatly increased risk, and the combination gets dangerous at lower levels than scientists previously believed,” the scientists said.

To answer the question of “How hot is too hot?” the scientists brought young, healthy men and women into a lab at Penn State University to “experience heat stress in a controlled environmental chamber.” Each participant swallowed a small telemetry pill that monitored their core temperature. They sat in an environmental chamber, moving just enough to simulate the activities of daily living, while researchers increased the temperature and humidity around them. The scientists found the study subjects’ “upper environmental limit” was even lower than a previously theorized 95 degrees Fahrenheit. “It occurs at a wet-bulb temperature of about 87 F across a range of environments above 50% relative humidity. That would equal 87 F at 100% humidity or 100 F (38 C) at 60% humidity,” the scientists reported.

“Current heat waves around the globe are exceeding those critical environmental limits, and approaching, if not exceeding, even the theorized 95 F (35 C) wet-bulb limits,” the scientists said. “In hot, dry environments the critical environmental limits aren’t defined by wet-bulb temperatures, because almost all the sweat the body produces evaporates, which cools the body. However, the amount humans can sweat is limited, and we also gain more heat from the higher air temperatures.”

The danger heat and humidity bring: “When the body overheats, the heart has to work harder to pump blood flow to the skin to dissipate the heat, and when you’re also sweating, that decreases body fluids,” the scientists said. “In the direst case, prolonged exposure can result in heat stroke, a life-threatening problem that requires immediate and rapid cooling and medical treatment.”