The Real Reason Seabirds Survive Typhoons by Flying Into Them

Birds manage to survive by pushing their luck.

Some seabirds have a survival instinct that might seem unusual—faced with typhoons, they fly directly into them. A recent study explained what’s behind this phenomenon and how these birds manage to survive by pushing their luck. Read on to find out more, like how many birds seem to develop this counterintuitive skill.

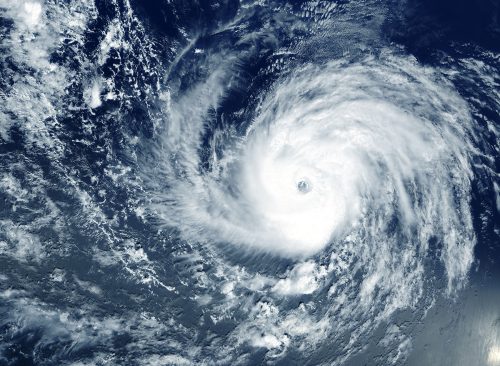

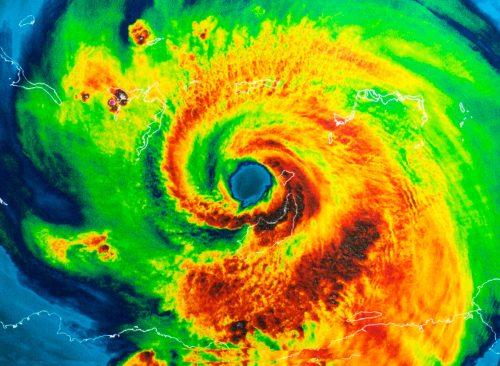

A new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that seabirds known as streaked shearwaters that nest on islands near Japan sometimes fly directly toward passing typhoons. There, they literally ride out the storm, flying near the eye for hours at a time—behavior that hasn’t been observed in any other bird species. It seems to be a strategy they’ve developed to survive massive storms.

Many birds will turn tail when a huge storm approaches, making efforts to avoid its track or fly in the other direction. But certain seabirds live in areas where “there is literally nowhere to hide” from storms, said Emily Shepard, a behavior ecologist at Swansea University in Wales.

To look at the shearwater’s reaction to cyclones, Shepard and a team analyzed 11 years of data from GPS trackers attached to the wings of 75 birds nesting on Awashima Island in Japan. They found that some of these birds would actually veer off their usual flight patterns and head toward the center of an approaching storm.

The researchers found that in the group of 75 tracked birds, 13 flew to within 37 miles of a storm’s eye—an area where the winds were strongest—for up to eight hours, following the cyclone as it moved north. “It was one of those moments where we couldn’t believe what we were seeing,” Shepard said. “We had a few predictions for how they might behave, but this was not one of them.”

The scientists found that the shearwaters were more likely to head for the eye during stronger storms. It suggests that the birds might be following the eye to avoid being blown inland, where they might crash onto land or get hit by flying debris, Shepard said.

“We know very little about how seabirds respond to storms, because this kind of extreme weather is, by definition, a rare event. And no two storms are the same,” Shepard wrote on the Conversation. “The strategy of flying towards the eye is probably only an option for fast-flying, wind-adapted birds such as albatrosses and shearwaters. We will need more data to understand whether and how seabirds with different flight styles and energy costs respond to typhoons that are increasing in intensity, as well as potentially in size and duration.”