Elon Musk’s Starlink and Other Satellites Could Harm the Environment, New Report Warns

"An essentially unmitigated disaster."

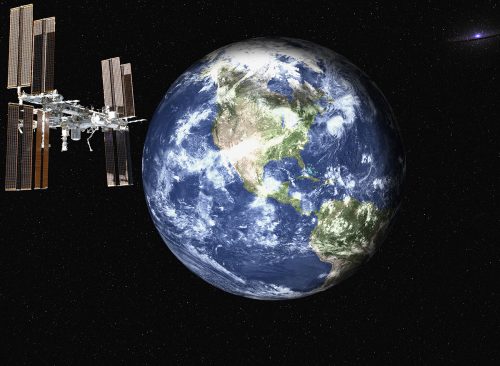

A new era in space exploration is underway—and while experts are hailing the launch of NASA’s Artemis I rocket, excited about the new discoveries that will enable, other developments aren’t being greeted with enthusiasm. Some scientists say one, in particular, could inhibit science and damage the environment. It’s the rise of satellite mega constellations, like those launched by Elon Musk. Mega constellations are “vast groups of spacecraft, numbering in the thousands, that could spark a multitrillion-dollar orbital industry and transform global connectivity and commerce,” says Scientific American.

The era started in 2019 when Musk’s SpaceX began launching its Starlink satellites into low-earth orbit. In three years, more than 3,000 have been deployed. Read on to find out what the satellites are intended to do and why some scientists say they could cause real problems for the environment.

RELATED: The 10 Most “OMG” Science Discoveries of 2022

Starlink is a venture by SpaceX to beam high-speed broadband Internet to all areas of the planet via communications satellites. The company ultimately plans to build and maintain more than 12,000 of those satellites in low-Earth orbit. A competitor, OneWeb, has plans for its own network of 650 satellites, and Amazon’s Project Kuiper constellation will number 3,000. Some estimate 50,000 satellites will be launched globally in the next few years. These constellations are essentially unregulated. Experts say if that doesn’t change, Earth’s orbital environment could be damaged. “If you don’t take action now, then you will be as responsible as those who have not taken care of climate change,” says Kai-Uwe Schrogl, chief strategy officer for the European Space Agency.

Among the problems posed by mega constellations: They can appear very bright in the sky. “For professional astronomers, they are on the cusp of becoming an essentially unmitigated disaster, regularly photobombing the delicate observations of facilities on the ground and even ones in low-Earth orbit, such as the Hubble Space Telescope,” says Scientific American. Radio communications from those satellites can also interfere with radio astronomy instruments, which need quiet skies to record the distant universe. Failed satellites could increase the amount of space debris in orbit, causing collisions.

The launch of satellites is approved by the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC). But last year, Ramon Ryan, a Vanderbilt law student, pointed out that this policy may violate environmental law, specifically the 1970’s U.S. National Environmental Policy Act. Ryan argued that the night sky’s natural aesthetic and astronomy itself may be protected under NEPA. The FCC was exempted from NEPA’s oversight because of a “categorical exclusion” granted in 1986 when the volume of satellites being launched was much smaller. Because of his paper, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) took up the issue and released a report this month.

In its Nov. 2 report, the GAO said the FCC should review the effect mega constellations have on the environment, revisit its exclusion from the environmental act and potentially update its procedures to address the era of mega constellations. “We think they need to revisit [the categorical exclusion] because the situation is so different than it was in 1986,” said Andrew Von Ah, a director at the GAO and one of the report’s two lead authors.

The White House Council on Environmental Quality recommends that agencies revisit categorical exclusions every seven years; the FCC hadn’t done it since 1986. A major issue that needs clarification: What exactly is the “environment,” and does low-Earth orbit qualify? “This is the question,” said Von Ah. “We didn’t opine whether it does or does not. What we were focused on was the FCC’s process for making those determinations.”

The FCC said it had reviewed the report. On Nov. 3, it announced it was creating a new bureau for its space activities, which will help the agency handle the applications for 64,000 new satellites that are currently in its inbox. “The new space age has turned everything we know about how to deliver critical space-based services on its head,” said FCC Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel in a statement. “The organizational structures at the agency have not kept pace as the applications and proceedings before us have multiplied, and in some cases exponentially. And you can’t just keep doing things the old way and expect to lead in the new.”